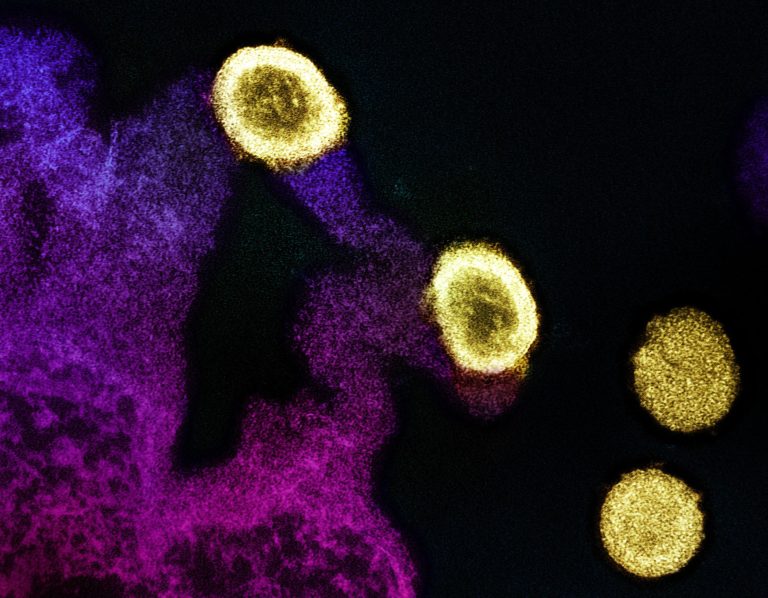

In a groundbreaking clinical trial, semaglutide has emerged as a potential game-changer in the fight against liver disease in individuals living with HIV. The study, conducted internationally with support from various health institutions, has demonstrated that semaglutide can safely reduce liver fat by an impressive 31% in patients with HIV and Metabolic Associated Fatty Liver Disease (MAFLD).

The significance of this trial cannot be overstated. Liver disease, particularly MAFLD, poses a significant health risk for individuals with HIV, who are already vulnerable to a myriad of complications. Historically, treatment options for MAFLD in this population have been limited, and the need for effective interventions has been urgent.

Semaglutide, a medication commonly used to treat type 2 diabetes and obesity, has shown promising results in addressing liver fat accumulation in this specific patient group. The trial not only demonstrated a substantial reduction in liver fat but also observed improvements in weight, blood sugar levels, and triglyceride levels among participants.

These findings underscore the potential of semaglutide as a multifaceted therapeutic agent for individuals with HIV and MAFLD. By targeting both liver fat accumulation and metabolic abnormalities, semaglutide offers a comprehensive approach to managing the complex interplay of factors contributing to liver disease in this population.

What sets semaglutide apart is its mechanism of action. As a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist, semaglutide works by stimulating insulin secretion, suppressing glucagon secretion, and slowing gastric emptying, thereby improving glycemic control and promoting weight loss. Additionally, emerging evidence suggests that GLP-1 receptor agonists may have direct beneficial effects on liver metabolism, making them particularly promising candidates for the treatment of MAFLD.

The safety profile of semaglutide observed in this trial is also encouraging. Adverse events were generally mild to moderate, with gastrointestinal symptoms being the most commonly reported side effects. Importantly, there were no significant differences in adverse events between the semaglutide group and the placebo group, suggesting that semaglutide is well-tolerated in this population.

Moving forward, further research is needed to fully elucidate the long-term efficacy and safety of semaglutide in individuals with HIV and MAFLD. Additionally, studies exploring the optimal dosing regimen and potential interactions with other medications commonly used in this population will be essential.

Nevertheless, the results of this trial represent a significant step forward in the management of liver disease in individuals living with HIV. Semaglutide offers new hope for patients and clinicians alike, providing a promising avenue for addressing a critical unmet need in HIV care.

As research in this field continues to evolve, semaglutide stands out as a beacon of progress, offering the potential to transform the lives of those affected by HIV-related liver disease. With continued dedication and collaboration, we may be on the brink of a new era in the management of this complex condition, where vanishing fat signifies not just a triumph over disease but a brighter future for all.